Even among all the fiercely offbeat singers who sprang out of modern jazz in the 1940s and ’50s, Sheila Jordan stood out. Her sound, she admitted, “took some getting used to.” It was high, fluttery and featherweight, yet trimmed with a bluesy wail. Native American chant-like runs — she had Cherokee blood — burst out of her. So did a bebop vocabulary learned straight from the creators, notably Charlie Parker, her idol and friend since her teens.

That voice carried Jordan throughout a nearly 80-year career. It took her to countless countries, yielded dozens of albums and earned her a 2012 Jazz Masters Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Just months before August 11, 2025, when Jordan died in Manhattan at 96, she was still singing.

To anyone who met her or saw her perform, she was an ever-youthful beacon of positivity. Jordan was also a tireless cheerleader for bebop — a music, she said, that had saved her life early on. “I went to bed with it, I woke up with it,” she told me in a 1998 interview. “Nothing else seemed to matter to me. I was totally addicted to bebop. I think it was the emotion. God, when Fats Navarro played a solo, it made my hair stand up. I could sit and cry when Bird played. Tears of everything, joy, pain, sadness.”

Besides bop, Jordan tackled avant-garde and free jazz with a blitheness that made them sound easy. She pioneered the format of jazz voice and solo bass, first with Charles Mingus but most famously with Harvie S, with whom she shared a telepathic rapport. With no drummer to keep time and no pianist to steer the chords, Jordan sang as she lived, without a net.

Her bravery captivated younger singers, notably Theo Bleckmann, her celebrated protégé and one of her closest friends. “She had a dedication to a craft and to a way of living that doesn’t exist anymore,” he says. “Everyone who met Sheila thinks of her as their mother, their guiding spirit.”

Jordan exuded empathy, for she had survived hellish struggle and loss. She tapped into them when she sang “The Water Is Wide,” a folk song with an almost biblical depiction of a challenged soul calling out for help: “Give me a boat that can carry me through.” Taking it at the slowest possible tempo, she stretched its phrases to the limit. Every bent note held an ache; she let her voice coarsen and crack, hiding nothing.

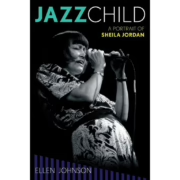

A 1995 documentary about Jordan, Cate Bursell’s In the Voice of a Woman, and Ellen Johnson’s 2016 biography Jazz Child: A Portrait of Sheila Jordan, leave no doubt that she had lived her every song she sang. “I’ve been singing since I was two or three,” she told me, “but not because I wanted to be a singer. When you’re in a lot of pain, something about the music pulls you through.”

A 1995 documentary about Jordan, Cate Bursell’s In the Voice of a Woman, and Ellen Johnson’s 2016 biography Jazz Child: A Portrait of Sheila Jordan, leave no doubt that she had lived her every song she sang. “I’ve been singing since I was two or three,” she told me, “but not because I wanted to be a singer. When you’re in a lot of pain, something about the music pulls you through.”

First Solo

Jordan was born Sheila Jeanette Dawson in Detroit on November 18, 1928. Her birth father was an illiterate factory worker; he married her teenage mother the night she birthed Sheila in a Murphy bed. Then he vanished. Both parents were alcoholics; the disease plagued her family. “My mother eventually died from it,” Jordan said.

She was sent to live with her grandparents in Summerhill, Pennsylvania, an impoverished coal-mining town. They existed on welfare in an ill-heated house; food and clothes were often scarce. “There were so many mine explosions that I got over the fear of death,” said Jordan to writer Burt Korall in 1980. “I saw it as inevitable, something that could happen at any time.” When she sang at PTA meetings or on the street, local kids ridiculed her high-pitched voice. Their bullying made her all the more determined.

In her early teens she moved back to her mother’s house in Detroit. Big-band swing was soon to give way to bebop; elsewhere in town, three of her contemporaries, pianists Tommy Flanagan and Barry Harris and guitarist Kenny Burrell, were working their way up. A sudden epiphany in 1946 set Jordan on her path.

Flipping through the pages of a jukebox, she spotted a single, “Now’s the Time,” by Charlie Parker’s Ree Boppers, a group she didn’t know. She fed a nickel in and pushed the button. “I heard a few notes and I thought, that’s the music I’ll dedicate my life to,” she said. Soon she was devouring all the bop she could find. “I had to scrub floors in order to buy a 78 record so I could go home and try to figure out, what are these people doing? I love this!”

Around that time Jordan met two African American singers, Skeeter Spight and LeRoy Mitchell, who scatted and wrote vocalese lyrics to Parker tunes. She asked if she could join them. The integrated trio sang anywhere people would listen. “I identified very readily with Black people,” she told Korall. “For years I would go around telling people I was Black. I really felt Black. I was totally involved with jazz music, and I felt I had come into a race of people who understood.” But she never tried to imitate her Black colleagues. Decades later, Theo Bleckmann marveled at how Jordan had “built her own sound as a white singer in a predominantly Black world without apology, without pandering, without trying to be anything but herself.”

Nonetheless Jordan had stepped into a danger zone, for riots were erupting in Detroit and color lines were not to be crossed. “I got harassed by white people, beaten up,” she told me. “I got constantly stopped by the cops, constantly taken to the police station.”

No one could keep her from Charlie Parker. When he came to town, a still-underage Sheila, accompanied by Spight and Mitchell, showed up with fake ID. The doorman threw her out. She and her friends went to an alley in the back and listened to the saxophonist through a window. On his break, he stepped outside. “He saw these young kids looking up at him, idolizing him,” she recalled. “He said, ‘Oh my God, do you want to hear me that badly?’”

Parker became a mentor to her; he even gave her a royal benediction by telling her she had “million-dollar ears.” But she knew she had a lot to learn. Moving to New York, she took lessons with the bop pianist Lennie Tristano, an impassioned, opinionated teacher and nurturer of unusual talent. “He gave me strength to be unique in the way I sang,” Jordan said. “He let me know it was okay to be a little quirky.”

So driven was she to stay close to Parker that she embarked on a risky interracial affair with his pianist, Duke Jordan, who like Parker was a junkie. They lived together then married in 1952. Three years later, while Sheila was pregnant, he deserted her. From then on he barely acknowledged Sheila or his daughter and sent no child support. Jordan never remarried.

On Her Own

Now a single mother, Jordan took a job as a secretary in an ad agency. Still she managed to thrust herself more deeply into jazz than ever. In her loft apartment on West 26th Street she welcomed some of the foremost players on the scene, including bassist Paul Chambers and saxophonist Sonny Rollins. “She just left it open for any good musicians who came into town and needed a place to stay,” says Harvie S.

She found her own safe haven in the late ’50s. The Page Three was a wacky Greenwich Village nightclub that songwriter Dave Frishberg, one of its resident pianists, called “a museum of sexual lifestyles.” It became Jordan’s unlikely launching pad.

Essentially a lesbian bar, the Page Three was mostly populated by gays, cross-dressers and thrill-seekers. The mafia owners kept cops at bay. Audiences watched variety shows that featured oddballs such as Bubbles Kent, a petite lesbian in a tuxedo who stripped down to a bra and G-string; and the long-haired future camp celebrity Tiny Tim, who played ukulele and sang 1920s ditties in a warbling falsetto. Mixed in was an incongruous array of fledgling jazz singers, including Mark Murphy, Morgana King, Ernestine Anderson and Beverley Kenney.

Jordan adored the club. “It was the only place I was accepted,” she told me. Announced by the emcee as “a new note in jazz,” Jordan sang lots of torch songs (“If You Could See Me Now,” “I’m a Fool to Want You,” “Am I Blue?” “Willow Weep for Me”), a little bop, and a few tunes by Oscar Brown, Jr., a singer-songwriter with a witty, eloquent take on life in that racially segregated age.

Audiences sometimes saw her singing in duo with Steve Swallow, a rising bassist. Jordan had first tried it in 1950, she recalled, during a Charles Mingus engagement at a club in Toledo, Ohio. He called her up to sing. The other musicians sat out as she and Mingus winged a duet of “Yesterdays,” a Jerome Kern-Oscar Hammerstein II showtune adopted by the beboppers.

Peter Ind, a British bassist who lived in New York and a collaborator of Tristano’s, dropped by the Page Three to hear Jordan. He invited her to make what would be her first issued recording, released in 1961: a single track, “Yesterdays,” on his album Looking Out.

Singing about a wistful look into the past, Jordan gave a performance that teemed with character. Her shivering vibrato, flurries of improvised notes and strange bop intervals all magnified the song’s drama. DownBeat went on to flag her as “a jazz singer who could be very important.” Frishberg recalled the response to Jordan at the Page Three: “Sheila was magic. The customers would stop gabbing and all the entertainers would turn their attention to her and the whole place would be under her spell.”

Her salary at the club, nine dollars a night, was eaten up by cab fare and Tracey’s babysitter. Jordan went home at four in the morning; five hours later she was at the office, typing. “If this is the way it has to be in order for me to sing the way I want then it’s OK with me,” she informed a reporter.

A subsequent crowd at the Page Three included pianist-composer George Russell, one of a vanguard of experimental post-bop artists. Russell had come to see Swallow, who was in his band, but it was Jordan who stole his ear. She told me what ensued: “He said, ‘Where do you come from to sing like that?’ I said, ‘I come from hell, man!’ He said, ‘Can I go visit you in hell? I said, ‘Yeah, you can.’ And I took him back to Pennsylvania.”

Off they drove to a mining town of her youth. In a coalminers’ pub, a codger who remembered her asked if she still sang “You Are My Sunshine,” the miners’ favorite song. Russell knew it well enough to play it on the bar’s battered upright as Jordan sang.

That moment planted the seed for her appearance on his 1962 Riverside album The Outer View. Russell turned that hillbilly tune into a 12-minute odyssey that traversed everything new in jazz. There are jarring, dissonant harmonies, abrupt shifts of key and tempo and an edgy New York vibe. Suddenly the band drops out and in comes Jordan, frail and breathy, pleading “Please don’t take my sunshine away” as dark atonal mayhem creeps in behind her.

She still had not made a solo album, nor was she pursuing one. Ruth Lion, then a singer at the Page Three, invited her husband Alfred Lion, cofounder of Blue Note Records, to hear Jordan.

A Blue Note Debut

A Blue Note Debut

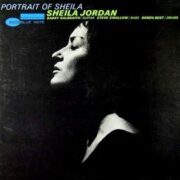

Thus was born her first LP, Portrait of Sheila, recorded in the fall of 1962. Jordan is commonly cited as the first singer to record on Blue Note, but the label had released two 1958 singles by Chicago jazz singer Bill Henderson with organist Jimmy Smith. A few months prior to Jordan’s album, singer Dodo Greene had made her own Blue Note LP, My Hour of Need.

But the honor of a debut on Blue Note spoke for itself. Jordan gathered her Page Three material and sang it in a shadowy, stark, late-night jazz-club setting created by Swallow, guitarist Barry Galbraith and drummer Denzil Best. Though fabled in retrospect, the album was no commercial hit; 13 years passed before her next. “I couldn’t get gigs at major jazz clubs,” she told me. “Now and then I did, on an off night, but I think they thought I was too far-out.”

With so much hurt to quell, Jordan inherited her family’s alcoholism. She called it “a periodic drinking problem. It wasn’t an everyday type of thing. Just weekends.” But according to Harvie S, who met her in 1973: “When she had one drink she couldn’t stop.” She traced the problem back to the Page Three, where customers kept sending her drinks.

Jordan remained high-functioning. Her advertising job yielded happy rewards when her employers hired her to sing major commercial jingles, for Whirlpool refrigerators, Thom McCann shoes, Bulova watches and other products.

As steady paychecks rolled in, she could afford to spend her off-time making whatever music she pleased, however uncommercial. Experimental musicians saw her as a muse. Jordan sang on the recording of Carla Bley’s jazz-rock opera, Escalator Over the Hill. She recorded with free-jazz trombonist Roswell Rudd and Aki Takase, a Japanese avant-garde jazz pianist.

On Steve Swallow’s ECM album Home, Jordan sang the verse of Robert Creeley — an American poet who credited Charlie Parker’s rhythm as an influence — in Swallow’s challenging settings. Her work in this period, says Theo Bleckmann, is “extremely modern, way beyond the standard jazz singing.” He notes her performance in Cosmopolitan Greetings, a jazz opera by the Swiss pianist George Gruntz and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg: “The music was extremely chromatic and hard and she nailed it.”

Amid all these guest appearances came her long-awaited second solo album: Confirmation, a Japan-only release on which she sang bebop and ballads. The band included Cameron Brown, another pivotal bassist in her life.

Amid all these guest appearances came her long-awaited second solo album: Confirmation, a Japan-only release on which she sang bebop and ballads. The band included Cameron Brown, another pivotal bassist in her life.

In the late ’70s, while touring in a quartet with pianist Steve Kuhn, drummer Bob Moses and Harvie S, Jordan coaxed the reluctant bassist into playing an entire duo concert with her. He agreed to do it if she would give him abundant time to rehearse. “We got five standing ovations,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Maybe we’ve got something here.’ It basically said to me, you’ve gotta re-learn how to play the bass. You’ve got to learn how to become an orchestra and make this interesting, instead of just going boom-boom-boom.”

Their duets became conversations. “I could do anything and she would respond, and I would do the same with her,” he says. Jordan saw their chemistry as magic. “I always feel when I’m working with Harvie that the angels are passing through at some point,” she told Robert Gaspar of Coda.

By now Jordan had quit drinking. “I had a spiritual awakening,” she told me. “I was on a couch and a voice came to me and said, ‘I gave you a gift. And if you don’t care of it I’m gonna take it away and give it to somebody else.’” She immediately joined a 12-step program. That episode inspired her to write the title song of her 1986 album The Crossing. It has the mournful, rootsy quality of the laments the coalminers sang in Pennsylvania. “If you search beyond the madness, there is peace of mind to gain … Take your troubles to the crossing/It’s where joy outweighs the pain.”

Jordan had been timid in one regard: She had clung to her day job, mostly out of concern for Tracey. But in 1987 she was laid off, and with Tracey heading toward an A&R career in R&B and hip-hop, Jordan knew it was time to fly free.

Ancillary income came from teaching, her second passion. Jordan had given workshops before; now she was offered a recurring post at the Institute for Jazz in Graz, Austria. There she met Theo Bleckmann, who was on his way to developing the ethereal, wordless style of improvisation with which he made his mark. He became the son she’d never had; she was his surrogate mom. But Jordan treated all her students maternally, whatever their talents. “In general she was extremely supportive of everybody,” says Bleckmann. “Nobody was excluded. She always said, ‘I don’t want to break their spirits.’”

Flowers for Sheila

Rewards rained down on her. In 1990 she began a long relationship with Joe Fields’s Muse label (later to become HighNote). On Lost and Found, Jordan sang with pianist Kenny Barron, Harvie and drummer Ben Riley. Heart Strings featured a string quartet arranged by Alan Broadbent. She also made numerous duo albums with Harvie S and Cameron Brown.

But hardship was never far away, and Jordan suffered a string of mishaps that in time struck her as almost comical. In 1996, her beloved country home in upstate New York was hit by lightning and burned down. She rebuilt it with the insurance money. Then the house was heavily damaged by a flood.

In Los Angeles to sing, she slipped on a banana peel and broke her kneecap. “Who slips on a banana peel?” said Jordan with a laugh. “That’s for comedians. To me it’s life. Shit happens!” She threw it all into “Sheila’s Blues,” her frequent closing tune, an improvised, semi-comedic yet prideful account of her life and times. After every show, fans bombarded her with praise. Her eyes would widen in disbelief. “Really?” she said.

Jordan would have been happy to circle the globe and sing forever, but her health was failing. In 2023 she made her last album, produced by Harvie S. in his home studio in the Bronx. Portrait Now, as it was called, revisited songs from Portrait of Sheila along with others of particular meaning to her.

Jordan would have been happy to circle the globe and sing forever, but her health was failing. In 2023 she made her last album, produced by Harvie S. in his home studio in the Bronx. Portrait Now, as it was called, revisited songs from Portrait of Sheila along with others of particular meaning to her.

Harvie and Roni, her steady guitarist in her last few years, provided the kind of stark background Jordan had sung to on Blue Note. Dot Time Records released the album in early 2025. Ben-Hur did all he could to help a weakened Jordan to carry on; he saw her as an angel of jazz. “Her sincerity, her honesty, her humility and servitude to the music were so inspiring,” he says.

The trio launched Portrait Now at the Green Mill jazz club in Chicago on February 14 and 15. Those were Jordan’s last shows. A few months later, Tracey — always her mother’s best friend — moved the seriously ailing singer to the Actors Fund Home in Englewood, New Jersey. When her Medicare coverage ran out and Jordan needed hospice care, Tracey brought her mother back to the apartment on West 18th Street where she had lived since 1964. A GoFundMe campaign raised over $100,000 to cover Jordan’s round-the-clock care. But she hadn’t far to go. “Sheila was listening to bebop when she just closed her eyes and died,” says Theo Bleckmann.

Two summers earlier I had interviewed her there for liner notes to Portrait Now. When I arrived, she and Cameron Brown were rehearsing for a show the next day. Once he left, Jordan sat next to me on the sofa and plunged into a lifetime of memories. She saw the humor in almost everything and couldn’t quite fathom the recognition that was flooding in. “I’ve been getting all these awards, which I’m always shocked by,” she said. “I tell them, ‘Do you have the right person? Are you sure?’”

Turning serious, she acknowledged: “I did wait a long time to have all this. I never thought I would.” I remarked that, unlike many performers, she had chosen gratitude over bitterness and art over ego. Jordan nodded. “When I teach I like to let singers know what this music is truly about. It’s not about money, it’s not about being a star. It’s about keeping the music alive. And it’s about that emotional thing — not being afraid to share what you’re feeling. I’ve been through a lot of what people are going through. If I can help them get out of it then I feel I’m doing something worthwhile in life.” JT