Our JazzTimes Sweeps Week concludes on the last Thursday of the month, with one historical release/reissue pick from each of our reviewers.

Wayne Shorter, The Soothsayer (Blue Note)

Wayne Shorter, The Soothsayer (Blue Note)

Shelved until 1979, The Soothsayer expanded Shorter’s group from quintet to sextet, departing in a sense from the Miles Davis vibe of Speak No Evil and harking back to Blakey’s Messengers, which Shorter had left for Miles’s band about a year before. This was Shorter’s fourth Blue Note session, tracked on March 4, 1965, bringing McCoy Tyner back to the piano chair following masterful turns on Night Dreamer and JuJu (Herbie Hancock played on Speak No Evil).

On trumpet is Shorter’s fellow recent Messenger Freddie Hubbard, with bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams on loan from the Davis quintet (all three played on Speak No Evil). James Spaulding’s alto sax recalls Jackie McLean or Eric Dolphy with Mingus, and that energy permeates the big three-horn frontline as well. Perhaps The Soothsayer was shelved because it seemed inconsistent with Shorter’s label output to date. The next one to see release was The All Seeing Eye, probably Shorter’s most avant-garde work, in late 1966.

Coming to light as they did 14 years after the session, the tunes on The Soothsayer are best known to connoisseurs. Guitarist Mike Moreno tackled “The Big Push” on his 2017 trio album 3 for 3 (Criss Cross). Shorter himself revived “Angola” for his expansive, Robert Sadin–produced 2003 Verve release Alegría, and the famed quartet with Danilo Pérez, John Patitucci and Brian Blade revisited the Sibelius adaptation “Valse Triste” on Footprints Live! (2002). An important source, then, giving Blue Note’s Classic Vinyl reissue much to capture in terms of sonic contrast and clarity. — David R. Adler

Miles Davis ’55: The Prestige Recordings (Prestige/Craft)

Miles Davis ’55: The Prestige Recordings (Prestige/Craft)

Before Miles Davis joined Columbia and revolutionized jazz with his atmospheric Gil Evans collaborations, Teo Macero–produced jam collages and post-Sly-Jimi noise funk, the same trumpeter-composer in the early ’50s joined the Prestige label, where he revolutionized jazz with his spacious, open take on hard bop, his signature use of a Harmon mute, and a relaxedly breathy phrasing that wasn’t altogether that relaxed after all.

Miles Davis ’55: The Prestige Recordings, a three-LP collection of 70-year-old sessions (?!) recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s early Hackensack, New Jersey studio, presents Davis’s historic First Quintet (with green-but-growing tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones) and shows how a myth becomes reality. With additional help from Milt Jackson, Ray Bryant, Oscar Pettiford, Jackie McLean and Sonny Rollins, the pugnacious, unsettled sound of the iconic trumpeter playing pop and still-fresh standards in and around 1955 is set in amber.

All 16 tracks are the stuff of genius, jazz and beyond. Yet what’s funny about hearing Miles ’55 — the year his voice broke, incidentally — recontextualized as such is how polite it sounds. The slow, slinking blues of “Green Haze,” the fast-dancing “I Didn’t” (both original Davis compositions), the cushioned bop bounce of “The Theme,” or “There is No Greater Love” with its clear cluster of ascending chords, somehow reminiscent of orderly dinner chatter between guarded tastemakers — we can sense something dramatic is afoot, but no one’s quite ready to pull the trigger, so instead we get the spry waltzing “A Gal in Calico.”

To be clear, I am not dissing Miles Davis’s first notably innovative music. No changes in the jazz continuum occur unless the skittering rhythm and icy trumpet glare of “S’posin’” happens first. The sweetly reminiscing “Changes,” complete with Milt Jackson’s wild-eyed vibraphone, raises and calls the aces-high invention of the post-bop aesthetic with a full house of tender emotion. The kissing proximity of Miles’s Harmon mute to the microphone on “How Am I to Know” and “I See Your Face Before Me” is as wowingly inventive as the first time George Barnes or Eddie Durham applied electric guitar on record.

Davis’s true costar where Miles ’55 is concerned, however, is the sound — choice selections from The New Miles Davis Quintet, Miles Davis and Milt Jackson Quintet/Sextet and The Musings of Miles, all given an amniotic fluid-bathed warmth, combined with the machete-cutting clarity of its tracks, remastered from the original analog tapes from Van Gelder’s loving hands. — A.D. Amorosi

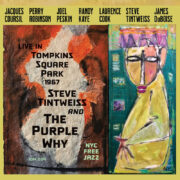

Steve Tintweiss and The Purple Why, Live in Tompkins Square Park 1967

Steve Tintweiss and The Purple Why, Live in Tompkins Square Park 1967

(Inky DoT Media)

For a time, bassist Steve Tintweiss’s official discography was limited to a handful of dates from 1965-70 with Patty Waters, Burton Greene, Frank Wright, Marzette Watts and most significantly Albert Ayler. But Tinweiss has expanded the list over the past several years through his archival label Inky DoT Media. In doing so he’s also fleshed out the catalogues of some of his peers, such as drummer Laurence Cook, trumpeter Jacques Coursil and clarinetist Perry Robinson.

Those three players appear on the latest discovery, Live in Tompkins Square Park 1967, along with then-soon-to-be prolific session saxophonist/bass clarinetist Joel Peskin, plus two somewhat obscure figures in drummer Randy Kaye (also piano) and (on one track) trumpeter James Duboise (best known for loft Studio We). Tintweiss is credited with all 12 compositions, which are often skeletal unison lines bookending long bouts of group improvisation in the raggedly exuberant style common to the period, played as two long segments across a 70-minute set.

Any chance to hear more of Robinson and Coursil, both no longer with us, is welcome. This earliest recording of Peskin shows a player quite comfortable in these avant-garde environs yet savvy enough to know their meager lucrative potential. The recording is a tad sonically uneven, so put on headphones, close your eyes and be transported to a very different era. — Andrey Henkin ◊