According to legend, Duke Ellington only fired one band member in the 50-plus years leading his orchestra. That oft-repeated story focused on bassist/composer Charles Mingus, who was unceremoniously terminated during his brief 1953 tenure with the band, when an argument broke out between the volatile bassist and Duke’s valve trombonist Juan Tizol. There are several versions of the story, but the one told most often was that a fight broke out onstage between the two. It’s been said that Tizol was brandishing a knife and Mingus ran after Tizol with a fire axe.

Whatever happened, Mingus was history after the incident. In his autobiography Beneath the Underdog, Mingus described the unique way in which he was terminated. “The charming way he says it,” Mingus wrote, “You feel like he’s paying you a compliment. Feeling honored, you shake hands and resign.”

The two did reconcile, after a fashion, during the 1962 recording of Money Jungle that featured Mingus, Ellington and Max Roach.

But far less known are two more Ellington firings that made less sense musically. Drummers Bobby Durham and Elvin Jones were both hired and fired during a late 1966 through early 1967 period when Ellington was searching for a drummer to replace Sam Woodyard. Either drummer, in one view, could have made a great deal of musical difference in the band.

Bobby Durham was a superb drummer, technically and otherwise, quickly making a name for himself in the 1960s, working in and around his native Philadelphia with rhythm and blues acts like Lloyd Price, and in Atlantic City with jazz organist Wild Bill Davis. According to Durham, Davis talked him into joining the Ellington band around 1967. Durham was initially hesitant, as he wasn’t thrilled about constant travel and the fact that in Ellington’s band, as he said, “There was a lot of music.”

Some who followed the Ellington band thought that the addition of Durham would give the band a shot in the arm. While Ellington seemed to be quite happy with the rickey-tick, backbeat style of Woodyard, who was in the band from 1955 to 1966, others maintained that Durham’s musicality and precise technique could swing the band in a fashion similar to how Louie Bellson was a rhythm section sparkplug when he joined in 1951.

Durham was with Ellington for five months, beginning in March of 1967. Ellington’s longtime alto saxophonist, Johnny Hodges, who rarely commented on anyone’s playing, loved Durham’s drumming, saying, “It’s been a long time since I heard a beat like that.”

For whatever reason, Duke Ellington just didn’t care for Durham personally or professionally. Mercer Ellington, who conducted the band for several years after his father’s passing in 1974, spoke candidly about the Durham situation in a 1980 interview.

“Duke used to ride Bobby,” Mercer said. “I don’t know what it was about Bobby. Duke was determined to really get this man to bend to his will or change his mind or something. Maybe Bobby was arrogant, but he knew his work. There was nothing about him that was not great, and really right for the band.

“Finally he fired Bobby. He just gave him two weeks’ notice. Bobby didn’t give a damn. He stopped trying to impress Duke and relaxed and played what he played and that was it. And Duke said, ‘How come he never played like that before?’ And then he told me to get him back. He hadn’t been out of that band for ten minutes before he was hired by Oscar Peterson.”

Durham stayed with Peterson for three years and then joined Ella Fitzgerald’s accompanying trio, occupying that chair for more than seven years.

In later years, Durham never discussed the incident in detail. He only said that Wild Bill Davis talked him into joining Ellington, and that he left because of the constant travelling. Though Oscar Peterson travelled as much or more than Ellington, Durham said that he joined Peterson because it offered more musical opportunities and because he felt it would be good for his career and visibility.

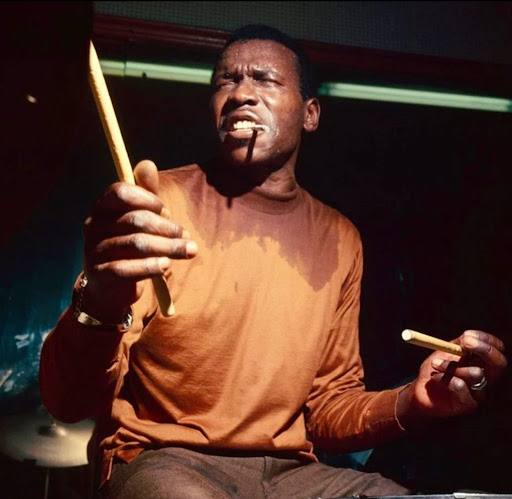

Elvin Jones left the famed John Coltrane Quartet in early 1966. He was increasingly unhappy with Coltrane’s musical direction at the time, nor was he happy working along with drummer Rashied Ali, who joined the quartet as second drummer in late 1965. Not long after he left Coltrane, Jones got a call from Stevie James, Duke Ellington’s nephew. In a June 2003 interview with Anthony Brown of the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program, Jones remembered the call he got from James: “Duke was looking for you and he wants you to come to Spain right away.”

Though Jones was unable to make it to Spain on such short notice, he did agree to meet up with the band in Frankfurt, Germany, for a tour managed by Norman Granz that also featured Ella Fitzgerald. Upon his arrival, he was surprised to find that Ellington already had a drummer. “What was I supposed to do?” he explained to Anthony Brown. “I just came out of a situation with two drummers! What are you trying to do to me?”

Ellington’s other drummer was a Philadelphian named Harry “Skeets” Marsh, who played with Milt Buckner, briefly subbed in the Basie band and taught in and around Philadelphia. Not only was he not very friendly, said Jones, but Jones was not actually asked to play until the band performed in Milan. From the time he arrived in Frankfurt until the band hit the stage in Milan, Elvin was being paid to be an “observer.” When he finally did perform, he had to play alongside Skeets Marsh.

“Marsh was playing drums with Duke like Lionel Hampton’s drummer would play, you know, the heavy backbeat,” Jones said. “I thought, ‘that’s terrible.’ I don’t know why Duke couldn’t have any better of a player who could assimilate or interpret a composition better than that. There were two drummers. And I was one of them.”

Though the drumming of Elvin Jones would have given the Ellington band an entirely new flavor, the whole idea, weird as it was, just didn’t work out. Jones lasted three weeks; Ellington paid him for six.

Jones, like Durham, put a positive spin on the experience, saying it was great playing with Ellington and that he enjoyed it. In retrospect, he believed he knew what Duke Ellington really wanted: “I know that if he had his druthers, he would rather have Sam Woodyard than anyone else in the world.”

In the end, Ellington hired Rufus “Speedy” Jones, a versatile, technical drummer who propelled any number of big bands, including those led by Count Basie, Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman. He was the perfect choice, staying with Ellington through 1972 when he was replaced by Quinten “Rocky” White, one of the last musicians to be hired by the maestro. JT