Hermeto Pascoal — the self-taught Brazilian wonder of jazz composition mixed with the sounds of his homeland, who modeled multi-instrumental prowess leading his own ensembles and contributing to albums from neighbors (Airto Moreira, Flora Purim, Edu Lobo) and American jazz giants (Donald Byrd, Miles Davis, Duke Pearson) — died on September 13, 2025, at the age of 89.

Suffering from the strains of lingering multiple organ failure, Pascoal passed away near his first home, in Rio de Janeiro. When the family announced his death on Pascoal’s Instagram page on Saturday, it asked his fans and followers “to let a single note ring — from an instrument, your voice, or a kettle — and offer it to the universe.”

No less than Miles Davis called Pascoal “the most important musician on the planet” and included three of Pascoal’s otherworldly compositions on his 1971 classic Live-Evil.

“The talent and tireless creativity of this Alagoan from Arapiraca made him internationally famous and influenced generations of musicians from around the world,” said Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a statement.

His output was prolific — over 2,000 instrumental pieces. But rather than one clearcut, particular style of playing or writing, Pascoal’s aesthetic was that of freedom — not free jazz but open-ended, zealous experimentation, mashing up baião, frevo, chorinho and samba with elements of classical music, musique concrète and polyrhythmic jazz, before people knew to call it that. This hurricane of multiple musics was like a hot wind banging against a wall of sound, then scattering like rain showers across Pascoal’s intricately arranged melodies.

Of his work, Pascoal once said, “I don’t play one style, I play nearly all of them.” He didn’t add, however, that quite often he played them, fluidly, all at once.

Where some saw eccentricity — welcoming live pigs into the studio during the recording of 1976’s Slaves Mass, blowing and pounding on household tools and utensils — others saw the visionary in him.

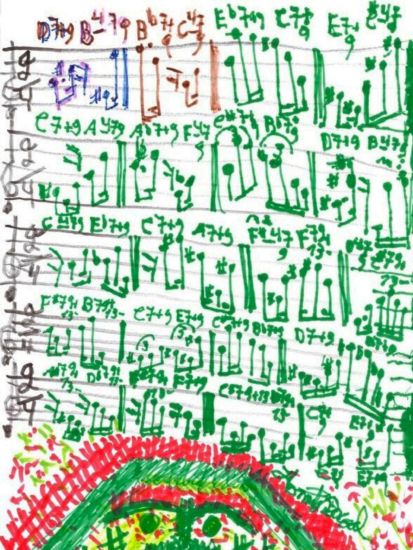

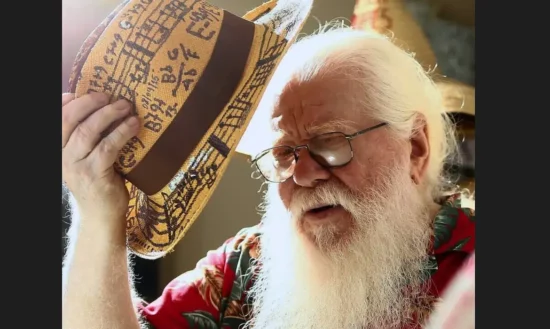

Upon presenting Pascoal with an honorary doctorate in 2023 at Juilliard School of Music, Wynton Marsalis referred to the childhood illness that nearly felled the young Brazilian native. “Even though your sight is impaired by congenital myopia, you are a compulsive composer with a constant flow of fresh ideas which you write on paper napkins, concert programs, hats — like the one you are wearing today — and that you draw like artwork on the walls that you pass. Every day, anyway, anywhere and everywhere, you write with intensity and with a burning, unquenchable fury…. Every musician who has worked with you throughout your long career has been forever touched by your magic.”

Upon presenting Pascoal with an honorary doctorate in 2023 at Juilliard School of Music, Wynton Marsalis referred to the childhood illness that nearly felled the young Brazilian native. “Even though your sight is impaired by congenital myopia, you are a compulsive composer with a constant flow of fresh ideas which you write on paper napkins, concert programs, hats — like the one you are wearing today — and that you draw like artwork on the walls that you pass. Every day, anyway, anywhere and everywhere, you write with intensity and with a burning, unquenchable fury…. Every musician who has worked with you throughout your long career has been forever touched by your magic.”

Born on June 22, 1936 in a rural Brazilian township, Lagoa da Canoa, Alagoas, Pascoal might not have been able to work on his family’s farm, but he excelled at the dexterity of musical instrumentation, starting off with the sanfona (button accordion), then moving onto flute and saxophone.

Before his teens, Pascoal played in ensembles with his father and brother, local dancers and weddings, before moving into a steady diet of forró gatherings, then a radio orchestra when he moved to Rio de Janeiro and became part of the glittering city’s nightclub jazz scene. By 1954, Pascoal may have been a wild musician, but he settled into marriage with the woman he became his muse until her death in 2000, Ilza da Silva.

After recording his first leader albums with various ensembles — his 1964 self-titled band work, Conjunto Som 4, Em Som Maior in 1966 with his Sambrasa Trio, Quarteto Novo in 1967 with his group of the same name — Pascoal made the wildly psychedelic Brazilian Octopus album in 1969. It was right at home within the Tropicália movement of Caetano Veloso, Os Mutantes, Gal Costa and Tom Zé.

B y 1970, the genius instrumentalist became part of the gently windy Brazilian jazz movement with contributions to albums from percussionist and bandleader Airto Moreira (Natural Feelings), Moreira’s wife, vocalist Flora Purim (Open Your Eyes You Can Fly) and singer-composer Edu Lobo (Cantiaga de Longe), as well as U.S.-branded jazz stars Donald Byrd (Electric Byrd), Duke Pearson (It Could Only Happen with You) and the aforementioned Miles Davis — all in 1970.

y 1970, the genius instrumentalist became part of the gently windy Brazilian jazz movement with contributions to albums from percussionist and bandleader Airto Moreira (Natural Feelings), Moreira’s wife, vocalist Flora Purim (Open Your Eyes You Can Fly) and singer-composer Edu Lobo (Cantiaga de Longe), as well as U.S.-branded jazz stars Donald Byrd (Electric Byrd), Duke Pearson (It Could Only Happen with You) and the aforementioned Miles Davis — all in 1970.

From that point on, “The Sorcerer” (or O Bruxo, as he was called) continued with a steady diet of his own albums — which often mixed unconventional household items to the instrumental whirlwind — and further experiments in sound such as Música da Lagoa’s water-immersive musicality with band members playing in a lagoon — while contributing too to the work of Sivuca, Elis Regina, Zé Ramalho and more.

Between 1996 and 1997, Pascoal created a book project, Calendário do Som, which welcomes a song for every day of the year (including February 29), and in 2003 was the subject of Serenata: The Music of Hermeto Pascoal, by Mike Marshall and former Pascoal band member Jovino Santos Neto. Vibraphonist Erik Charlston has also explored Pascoal’s music with his group JazzBrasil on the Sunnyside releases Essentially Hermeto (2011) and Hermeto: Voice and Wind (2019). JT