Beloved for creating the thunder behind Jackie McLean’s lightning for nearly 20 years until the alto legend’s passing in 2006, drummer Eric McPherson has never met a risk he didn’t like and make his own.

Perhaps such daring stems from his time with equally bold saxophonists such as Pharoah Sanders, Greg Osby and Abraham Burton, or percussive pianists such as Andrew Hill and Jason Moran. Deeper still, one could look at McPherson’s family lineage and its literal and figurative connection to the groove: Hill’s frequent bassist Richard Davis was McPherson’s godfather, the man who said this future drummer should be named after Eric Dolphy (another of Davis’s affiliates).

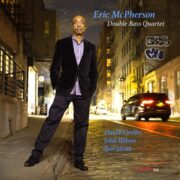

After a majestic start as a leader in 2007 with Continuum (Smalls Records), name-above-the-title duties with Duane Eubanks, Borderlands Trio with Kris Davis and Stephan Crump, Rez Abbasi, Lucian Ban’s Elevation with saxophonist Abraham Burton and bassist John Hébert — McPherson is back, leading the charge on the new album Double Bass Quartet – Live (Giant Step Arts).

After a majestic start as a leader in 2007 with Continuum (Smalls Records), name-above-the-title duties with Duane Eubanks, Borderlands Trio with Kris Davis and Stephan Crump, Rez Abbasi, Lucian Ban’s Elevation with saxophonist Abraham Burton and bassist John Hébert — McPherson is back, leading the charge on the new album Double Bass Quartet – Live (Giant Step Arts).

Together again with Hébert and another longtime four-string friend in Ben Street as well as heroic pianist David Virelles, McPherson delves deep into the psyche of drummer-leaders such as Max Roach and Elvin Jones, and by all accounts has a fantastic time doing it.

We caught up with McPherson right after album release day.

We’re nearly 20 years on from your debut leader album, Continuum. What do you recall about its impact on you and your still-forming aesthetic after Jackie McLean’s passing?

Looking back on Continuum, to make that session happen, required me to take on the roles of producer, engineer and musician. It was a great opportunity that allowed me to shine some light on the musical ideas I had happening at the time.

Along with your decade-plus with McLean, you also worked a lot with Andrew Hill and played on his final release, Time Lines [Blue Note, 2006]. What did these greats give you in terms of developing as a composer and leader?

Working with Jackie was an interesting challenge in that you had to have a knowledge and command of what came before without resting on it. You had to be present with whatever was happening. Drawing from past knowledge and information while finding your way to the right flow of what he’s doing right now. Jackie had a vocabulary that was evolving up until the end.

Working with Andrew presented a different challenge. Now you’re drawing from this same wealth of historical knowledge and again having to find the right flow for a situation, but with melody, harmony, rhythm … that may or may not be based in time. It may be a situation where time and no-time are working as one, together.

What was Richard Davis’s guidance for you like in regard to keeping time, and making time shift?

Richard’s impact on me was more from a cultural, conceptual and spiritual perspective. My mother brought me to meet Richard for the first time at Sweet Basil when I was around 12 or 13. Watching Richard’s group, which included the late, great [drummer] Freddie Waits [father of Nasheet], was my introduction to the music. I saw the dedication Richard had for the craft and his knowledge of the history. Coming up around Richard in my formative years, informed my musical sensibility more than words can describe. A tremendous voice in music history. It’s interesting that Continuum also featured John Hébert with a second bassist, Dezron Douglas. And now John is part of this Double Bass Quartet as well. What shared personal and artistic sensibilities allow you two to stand that test of time?

It’s interesting that Continuum also featured John Hébert with a second bassist, Dezron Douglas. And now John is part of this Double Bass Quartet as well. What shared personal and artistic sensibilities allow you two to stand that test of time?

The two-bass aspect on Continuum happened by chance. On one particular day, John and Dezron both showed up to the studio at the same time. Being a fan of the two-bass dynamic, I took advantage of the opportunity to incorporate that into the project. John and Dezron complemented each other beautifully, especially taking into account that they didn’t know they’d be playing together. Quite organic. At that point, the seed was planted in many ways for what would become the Double Bass Quartet project.

John and I worked together most notably with Andrew Hill, and later with the consummate pianist Fred Hersch. My rapport with John is such that anything is possible creatively and musically. I’ve also had the great fortune to work with Ben Street in many situations over the last 25 years. Around 1999 it was with Mark Turner and Kurt Rosenwinkel. More recently, there was the trio work with David Virelles, quartet work with Tom Harrell and Ethan Iverson, quintet work with Dayna Stephens. Ben brings a strong presence to any musical situation, which is why he is one of the preeminent bassists in creative music today.

Was there a set of songs you had for this group? A sound in your head?

I had done a number of recording projects with Jimmy Katz. He suggested documenting something a bit different than what we had done previously, so this provided the opportunity and truly opened up the double-bass door.

Was there a dueling vibe between the basses, a yin and yang? And could you talk about integrating your drums and Virelles’s piano into the mix?

I believe Ben and John naturally play in different parts of the bass spectrum. For me this lends to an organic blend. I wanted this interaction to be at the forefront, so my approach was to play in a way that wouldn’t override this dynamic, but be more complementary along with the piano.

I’ve been developing a rapport with David over the last 15 to 20 years. We’ve worked in duo format, trio with Ben on David’s recent album for Intakt called Carta. David has an advanced rhythmic, harmonic and melodic sensibility and a vast historical knowledge. He’s also a very creative and thought-provoking composer. “Transmission” is a tune I’ve had the opportunity to play with David in different configurations. I thought it would be a nice vehicle to explore with this format, and it adds a different dimension to the recording.

I’m a sucker for any Monk tune, so tell me about your choice of “Skippy.” And Stanley Cowell’s “Illusion Suite” is a tall order. How did that come to pass?

“Skippy” is one of those tunes you don’t come across every day, so you make it happen. When working with master musicians like Ben, John and David, you can play tunes like that and have fun with them, including tunes by Stanley Cowell. High-level democracy at work. JT