During a recent JazzTimes conversation with 8-Bit Big Band leader Charlie Rosen, the subject of Juan García Esquivel was raised.

Better known as Esquivel!, this eccentric Mexican bandleader, pianist and composer was famed for his breezily experimental compositions and nearly three decades worth of space-age lounge music. Additionally known as “The King of Space Age Pop” and “The Busby Berkeley of Cocktail Music,” Esquivel! — like Les Baxter, Martin Denny, Henry Mancini, even Dick Hyman (yes, the trad-jazz piano eminence once made exotica recordings on Lowrey organ and Moog synth) — created an idiosyncratic brand of airy instrumental pop with an astro-oceanic edge and more giddily quirky sound effects than a season of Lost in Space.

Though I won’t give away Rosen’s next set of Esquivellian moves, JazzTimes can make note of several other jazz-based musicians making delectably sweet-and-sour sounds in dedication to lounge exotica and space age bachelor pop.

Composer-bandleader Ryan El-Solh, of the band Scree, fashions his ensemble’s spacey symphonics to what he calls “spiritual lounge” music on the new full-length LP, August (Ruination Record Co.). Then there is Skip Heller, a multi-hyphenate Los Angelino who never met a vintage genre he didn’t like, and loves to manipulate, whose Voodoo 5 ensemble recently released its second tiki-torch-song tribute, Mojave After Dark.

These three musicians and their ensembles are effectively paving fresh roads for the new school of lounge exotica bachelor-pad jazz for the next age.

Wong, El-Solh and Heller shared responses, via email, to the question of how they move the (space) needle into a loungier future.

What other music have you played besides lounge music, and what led you down the exotica path?

Randy Wong: I have a career as a double bassist in the Hawaiʻi Symphony Orchestra, the oldest symphony orchestra in the U.S. west of the Rockies. I perform traditional and contemporary Hawaiian music, and I enjoy accompanying my father and his friends in their kīhoʻalu Hawaiian slack-key guitar and ukulele bands. Having been born and raised in Hawaii as a seventh-generation kamaʻāina of Chinese descent, I feel at home with the many musical traditions rooted here.

That said, it’s to exotica that I feel the strongest calling. Exotica was born from the multiple Pacific and Asian cultures prevalent in the Hawaiian Islands post-WWII; a musical tapestry akin to the racial, ethnic and cultural communities to which my family and I belong. Paying tribute to and helping to tell the story of this music is what led me to performing, perpetuating and presenting it. I also lead Red Nova, a free jazz trio, another form of marginalized music that’s filled with creativity and wonder.

Ryan El-Solh: I studied jazz in college, paving the way for my many subsequent years in the food service industry. That influence is still very present in the music I write for Scree. Picking music while bartending has also influenced my musical thinking — just seeing how people react to different things and what kind of moods I like to set in the room. I’ve also had the chance to play with some great songwriters on the Brooklyn scene. One group I play with, Office Culture, led by Winston Cook-Wilson, certainly has a lounge element to it as well.

Skip Heller: I’m a Philadelphia musician in my heart of hearts, so I’ve worked in everything from organ trios to Jewish wedding gigs, country music, oldies soul groups. Honestly, a lot of what led me in my teenage years to lounge music was chasing records — usually in thrift stores — that the B-52s cited as influences, like Henry Mancini and Yma Sumac, who I eventually played with. Those two lit the match for me.

When I heard Raymond Scott’s music, that was the burning bush just fully igniting. Scott made me rethink my whole musical life. I was also really taken with Carla Bley, Uri Caine, John Zorn, Don Byron, Burt Bacharach and Frank Zappa. That time, about 1992, was when I largely stopped playing in the bars in Philadelphia and started reexamining what I wanted to write and who I was going to get to play it. Before long, I wound up in Los Angeles, making this music.

Do you see lounge music as a form of jazz?

RW: Yes, absolutely. Lounge has many jazz roots, whether in its instrumentation and arrangements, its repertoire taken from show tunes and program music, and its popular appeal.

But it also has roots in classical music: Many pieces are miniature tone poems that are heavily inspired by the exoticism of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, the violin showpieces of Fritz Kreisler, the orientalism of Maurice Ravel or the visuality of Igor Stravinsky. Combining that with its jazz roots, in a way, makes for a Third Stream different from what Gunther Schuller and Ran Blake pioneered, but a magical blend of jazz and classical forms all the same.

RES: I don’t want to speak too broadly, but as far as Scree is concerned, we improvise melodically over forms in a harmonic language that comes out of jazz, but the rhythmic conception isn’t always coming out of jazz.

We also play some through-composed material that can feel more like something from a songwriter or like chamber music. If you listen to “Exclamation Point” from our last record, Live at the Owl Vol. 2, or “Either Way” on August, you’ll hear something a lot of people would identify as jazz. If you take a song like “TV Sometimes” on the other hand, I don’t know how many people would call that jazz. But honestly, I don’t feel invested enough in a particular definition of jazz to put my name behind it forever on the internet.

SH: It really depends on who’s playing it. If it’s me or Joey Altruda, it unavoidably is jazz, since we’re both steeped in that language. I think that jazz enriches the music, because it demands that the people in your ensemble stamp their identity on the performance, differently every time.

What was the gateway artist or album that inspired your particular style of lounge music and why?

RW: My introduction was through vibraphonist Arthur Lyman, who was an original member of the Martin Denny group that recorded Exotica, the album that launched the genre, and later led his own group. Mr. Lyman was a close friend of my grandfather, and as a young boy I heard him perform solo vibraphone.

Later, while in college at New England Conservatory, I took on a class project which led me to a CD that compiled several of Lyman’s albums. The CD was titled Music of Hawaii, but for me it was very confusing — it sounded nothing like the traditional Hawaiian guitar and ukulele music I had grown up with, but it used familiar Hawaiian melodies with a jazzy, exotic twist. And a ton of bird and animal calls, which I had heard Mr. Lyman make vocally when playing his solo vibes, but not in a band context. This led to more research, by which I learned about Martin Denny and Les Baxter, along with contemporary lounge groups like Combustible Edison and Don Tiki.

RES: In Line by Bill Frisell and Heaven Is Creepy by Jim Campilongo. In particular the song “Throughout” on the former and the instrumental version of “Cry Me A River” on the latter. Those records had a kind of emotional immediacy that I had missed while trying to learn to play more cerebral stuff in college, and they helped me realize that such immediacy was something I wanted to prioritize in my own playing and composition.

SH: The gateway album was Yma Sumac’s Voice of the Xtabay. The gateway artists were Henry Mancini for his compositions and Robert Drasnin for his mentorship. Obviously, Yma, Martin Denny and Les Baxter are always in there. But I’ve also been influenced by bandleaders from other styles of music — Bill Monroe, Eddie Palmieri, guys who knew what the blood of their music was but who also understood how to let the sidemen help shape the sound. Eddie Palmieri without Barry Rodgers or Bill Monroe without Earl Scruggs would be different. And less impactful.

How did your band start, and did you have a particular lounge sound that you wanted to pursue — something different, perhaps, than what your newest album portrays?

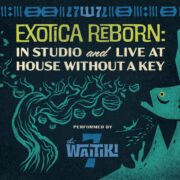

RW: The WAITIKI 7 started initially as a quartet of soprano sax/flute, vibraphone, bass and drum kit performing reductions of classic exotica that our co-founder and drummer Abe Lagrimas Jr. and I had transcribed and arranged, along with some of my own originals.

The originals were mainly based on standards that I’d either recomposed or reharmonized, often with added vocals, intros/outros, unusual instruments like melodica, marching machine and bass clarinet, along with storylines or visual elements to incorporate whichever friends I wanted to include at the time. Like a solfege-singing sumotori or a robot-dancing martial artist, for example.

In 2007-08, I was contacted by organizers at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, as they were planning the first summer of their Festival Wassermusik with a focus on exotica music. They asked if I would put together something special. My dream had always been an all-star septet of my virtuosic friends whom I felt could lend a real hand to performing classic exotica as it was done in the past.

RES: Scree started with no particular sound in mind other than the three of us playing. When we first started in 2016, I was basically listening to the Pinegrove records Cardinal and Everything So Far on repeat, and that influence is reflected in some of the music from that time. We would also play free improvisations and American songbook ballads.

In the nine years since we’ve absorbed a lot of different music. I listen to a lot of classical and Arabic music, which have made their way into our sound. As has the influence of the many great songwriters and players we’re surrounded by here in New York, particularly around the Owl Music Parlor, run and curated by Oren Bloedow. Maybe you could call us Owl-core.

SH: Voodoo 5 started because I went to exotica festivals where I heard very little actual exotica, more rock groups who had a nominal exotica influence, but nothing with the deeper command of harmony or Latin rhythms that marks Drasnin’s or Baxter’s music, so I decided that I’d better make it myself if I wanted to hear it.

My wife Lena’s five-and-a-half-octave range gave me a whole instrument to write for. I started with that and mallet percussion as the core, then added a Latin rhythm section and flute. The only thing out of the ordinary was steel guitar, but Alvino Ray had played a futuristic steel style on some ’50s albums that gave me clues.

This is not your first go at lounge music or the space-age oceanic bachelor pad sound. How and why did it morph into what the new album is, especially you, Ryan, with what you’ve self-titled as “spiritual lounge” music.

RW: Our first performance of The WAITIKI 7 was July 2008 in Berlin. Over the last 17 years, we’ve each evolved as musicians but have been able to take the time when meeting together to advance our brand. In recent years, reedman Tim Mayer, who we affectionately call the Mayor of Exotica, has taken up the mantle of composing and arranging and now contributes the majority of works to our book.

Tim found a love for writing and arranging through his close work with Robert Drasnin, the CBS Music Director who composed and led his own exotica album, 1959’s Voodoo, and who later scored incidental music for Hawaii Five-0. We prepared Robert’s music for concerts with Robert conducting and on clarinet in San Diego and Los Angeles.

Several members of the August ensemble — Luke Bergman, Ivan Arteaga, Carmen Quill and me — have roots in the experimental music scene in Seattle, particularly a series called Racer Sessions that ran from 2010 to 2024. The improvisational language of that scene continues to be a huge influence on everything I do musically.

SH: The first Voodoo 5 album was song-oriented. The band had only done one gig when we made the record in October ’23, so I stuck to a more conventional path. But Mojave After Dark, our second album, which we recorded around September 2024, is a personal travelogue.

Before we end, is there anything else you wish to say about lounge music as a phenomenon?

RW: To combat the threats of AI, sameness, homogeneity, we need to lean into what is special [about culture] more than ever. In doing so, we can model for the next generation that advocacy makes a difference.

Abe, Lopaka, Helen and I live in Hawaii, the middle of the Pacific. We want to show youth here that their dreams can come true. … All of us in The WAITIKI 7 are modern musicians, we equally and fluidly find ourselves as artists, teachers and scholars. [We want] to introduce … them to the knowledge of this very special music that brings together multiple genres, traditions, cultures and vocabularies. JT