In January of 2015, guitarist Hans Ottsen settled into The Beanpot Studio in West Orange, New Jersey to create what would become Navigation. A yearning to record a trio date with acclaimed veteran bassist Drew Gress and drummer Don Peretz had brought the Californian eastward, back to a place of importance in his journey, and the material he chose for the occasion — cloistered originals, choice covers, imaginative contrafacts — was of a piece with his personality, musical and otherwise.

“I was impressed with the patience in that music,” Gress notes, “and how it was all about hearing and conversing, really no ego.” A decade later, and three years after Ottsen tragically took his own life, his music, spirit and story deeply resonate.

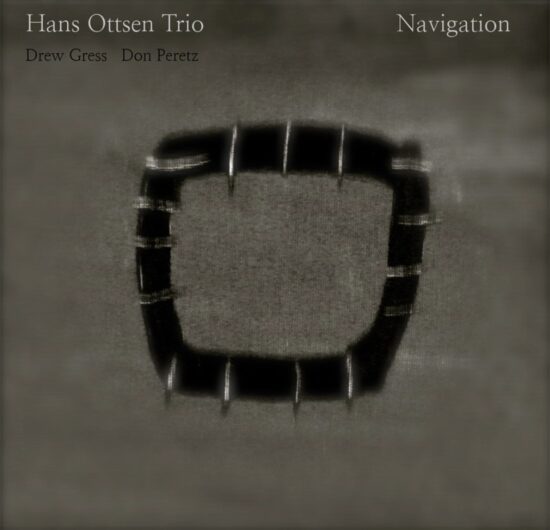

The artwork that adorns the front of the album — one of Peretz’s paintings, occupying a notable space on a wall in his home — held easy appeal for Ottsen. “He wanted it as the cover,” the drummer explains. “He saw that as a porthole out.” It was a telling interpretation from the guitarist, who long struggled with mental health issues. For Ottsen, the image offered a view of exterior possibility. But for listeners it serves as a window in — to the soul of a pained artist and the depth of his music.

Life on Two Coasts

Ottsen was born July 18, 1976 in Washington D.C. and raised in a musical household in Ventura, California. After a brush with singing and some studies on piano, he came to the guitar during his teen years and never looked back. First it was the draw of the blues and then jazz. Ottsen went on to study at the University of Southern California, where he and Peretz met. After a short time they each traded coast for coast, one unintentionally following the other, with both ending up at the Manhattan School of Music.

During Ottsen’s Big Apple stretch — eight to ten years straddling the new millennium, as Peretz counts it — the two bonded as friends and fellow travelers, cutting their teeth as touring musicians, crossing the pond in a trio with another California connection, multireedist Sam Sadigursky.

“I was lucky to spend a lot of formative times with Hans both in LA and later on when we were both students in New York,” Sadigursky recalls. “My very first trip to Europe was with Hans and Don in 1998 or 1999. Hans had a lot of family in Denmark on his father’s side and they set up a week or two of small gigs for us playing trio with the same instrumentation as the Paul Motian trio [with Bill Frisell and Joe Lovano], which we all idolized. We were so young, and this was sort of our version of the European backpacking trips that kids would do in college, except we had our instruments and were playing most nights.”

Those New York years were pivotal, but severe personal strain was right there all along. “Hans struggled with bipolar disorder his whole life,” Peretz shares. “As his close friend I pulled him out of a lot of holes, as he did for me.” Sadigursky is on a similar wavelength: “Hans’s playing deeply embodies who he was as a person — thoughtful, patient, smart and selfless. There was a lot of suffering in his life, and music was a deep place of comfort and respite.”

As Ottsen’s sister Mollie Benton explains, Ottsen wrestled with how to control his condition while fulfilling his artistic desires. Medication helped, but it suppressed creative impulses in the process.

Eventually, Ottsen felt home calling and left New York for Ventura, creating a vital scene over time in that coastal haven. Along with playing and teaching, he hosted a jam session at The Squashed Grape and loved organizing and producing house concerts under the “Jazz on the Lane” banner, which contributed to a jazz renaissance for the entire area.

Ottsen’s teacher and friend Gilad Hekselman fondly recalls the experience of performing at his concert series in later years: “When Hans heard I was coming out to the area he invited me. And it was such an amazing community and unique experience there. You share a family meal, you play a concert, then you hang out and sip whiskey and pick some avocados at the orchard. It was a very different kind of gig, just beautiful.”

Navigation

Ottsen was firmly ensconced in that idyllic setting, where live music came to thrive through his efforts. But he felt drawn toward the studio. Despite his highly self-critical nature, Ottsen began to experiment in that realm, releasing the results as Music for Mind Movies in 2014. Shortly thereafter he hatched a plan to return to New York to turn his trio dream into a reality.

Drew Gress, enlisted for the Navigation session, noted the instant click that came in the short leadup to it: “Hans was a special kind of player and person. It was really easy to develop a rapport with him. In retrospect, hearing the album again now, I’m struck by how patient he was, and the way he’s tuned into the group picture, the bigger picture.”

That simpatico is clear from the outset on the Ottsen original “Jonathan Cooper.” The feisty swing of “You Choose Blues” takes things in a different direction, offering both shades of influence and individuality. “It was Monk who influenced that tune,” the drummer notes. “Hans was an absolute encyclopedia. He’s thinking Paul Bley too. This honors that aspect of Bley’s music and the blues in general.”

The title track — “a tiptoe through paranoia,” as Peretz puts it — navigates anxiety, the uncertain allure of the music mirroring a trip through a minefield in the mind. Then comes Boudleaux Bryant’s Everly Brothers–associated “All I Have to Do Is Dream.” Recast in five for most of it and delivered without a touch of irony, it owes a debt of gratitude to the Frisell/Driscoll/Baron aesthetic while also speaking directly to Ottsen’s own appreciation for direct engagement.

“Squealar,” the leader’s contrafact on “Solar,” is purposefully playful and driving. “Shea’s Dream,” a star-kissed ballad in three, is a Strayhorn-esque soother, a dedication to Ottsen’s nephew. “Olive Stings You Arm” is a play on “All the Things You Are.”

The album closes with the bucolic draw and gentle train beat of “Zoë’s Lullaby.” “Hans wrote that for his niece,” says Peretz. “He loved his nieces and nephews.” Benton recalls the light he brought to their lives: “My four kids remember him as the best uncle imaginable, playful and full of life, always ready to join in their games as if he were one of them. When he showed up, he showed up big, overflowing with love and spirit.”

Reflection

When Navigation was released on July 16, 2015, it hardly made waves. Ottsen’s self-consciousness surrounding his work led him to avoid PR of any kind. The digital-only format had little chance on the airwaves. In addition, music with measured purpose — that “whispers more than shouts at you,” as Gress puts it — often gets lost in the din. “It’s just ironic to me that some of the deepest music has the hardest time emerging,” Gress elaborates. “Subtlety doesn’t seem to be the way in the world today.”

Navigation is a quiet standout, and that’s what drove Peretz to reissue it on its tenth anniversary. “I feel that people need to hear Hans, and he disappeared too soon.” Beyond the music, Ottsen’s story imparts a message for those dealing with similar struggles. “Our relationship had its challenges, a rollercoaster of highs and lows,” his sister Benton remembers. “But through it all, there was a magic in him that was impossible to deny. With the rhythms of his bipolar disorder came moments of brilliance — flashes of light that left a mark on everyone around him. He drew incredible people into his orbit, and his musical talent was simply undeniable. His legacy keeps playing on in all of us who were lucky enough to know him.”

“There was a sensitivity and output from Hans like no other human being on Earth,” says Peretz, “and with him gone, I’m left wondering if it’s all of us that are actually missing something. It seems that love and singular artistry are fleeting. So maybe we can do a better job of keeping them here with us for as long as possible. We need them more than we know.” JT