Jim McNeely, who played piano with many legends of jazz before becoming one of the most important large-ensemble jazz composers of his generation, has died of bile duct cancer at 76 at home in New York City. His death was confirmed by his wife, Marie McNeely.

McNeely had been in the forefront of advanced big-band composition since the mid-1980s. As mentored directly by jazz luminaries Thad Jones, Mel Lewis and Bob Brookmeyer, he became a key contributor to the repertoire for Monday nights at the Village Vanguard.

McNeely then took that American tradition to the big bands of Europe, including WDR (Cologne), UMO (Helsinki), the Stockholm Jazz Orchestra, the Metropole Orchestra, the Danish Radio Big Band and the Swiss Jazz Orchestra (Bern). A particularly long and fruitful relationship was with the Frankfurt Radio Big Band.

In America, McNeely stayed connected to the Vanguard band; he also worked with the Carnegie Hall Jazz Band and many student groups and even spent 16 years as the music director for the BMI Jazz Composers Workshop. He created the paradigm for bringing fresh new ideas about line, harmony, rhythm, sound and musical architecture into the vocabulary of large-ensemble jazz.

Many McNeely compositions contained fleet saxophone melodies over skittering, sometimes ominous syncopated bass lines, while the lyrical element would be supplied by sustained brass shapes written against the beat. While this was all quite creative and complex, each section of the band was tasked with the playable, not the impossible, and an eight-minute chart would unfold as naturally as a cell division.

The compositions simply poured out of the man, and over time McNeely’s reputation attained legendary status among big-band insiders. He received 12 Grammy nominations, winning one with the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra in 2008. By now his legacy is not just secure, but continuing to influence the work of big-band composers. The acclaimed composer Maria Schneider noted, “Jim leaves the world a tremendous amount of music. I and others will continue to discover and study it, play it, marvel at it and just love it.”

Jim McNeely was born in Chicago and attended the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana. The impressive youthful local scene surrounding U of I in that era included trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater, saxophonist Ron Dewar and educator Robert “Doc” Morgan. In the late 1960s, while still a teenager, McNeely appeared in DownBeat a few times, as an upcoming composer of note and as the author of an Ornette Coleman transcription.

McNeely moved to New York in 1975 and soon established himself as a young firebrand with a piano style informed by the heroes of the 1960s including McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea. While this cutting-edge approach perfectly aligned with other forward-thinking contemporaries like David Liebman and John Scofield, McNeely was also a grounded and flexible player who could fit in with an older generation, enabling him to hold down multiple-year tenures in the working bands of first Stan Getz and then Phil Woods.

The most transformative gig started in 1978, when McNeely started playing Monday nights at The Village Vanguard in the big band co-led by Thad Jones and Mel Lewis. Jones left in 1979, leaving Lewis in charge with the innovative Bob Brookmeyer as music director.

During its heyday in the 1930s and ’40s, the big band was for dancing, drinking and partying. After the hubbub died down and the general listener moved on to rhythm and blues and rock-n-roll, a few composers kept tinkering, turning the big band into a laboratory to create advanced formal structures within the jazz idiom.

Trombonist and conceptualist Bob Brookmeyer was one of the key figures in this progressive approach, and in McNeely he found a kindred spirit, a youngster ready to keep pushing his lineage forward. McNeely later said of Brookmeyer, “I was very lucky that this generous man saw something in me and challenged me to develop what he saw as my talent.”

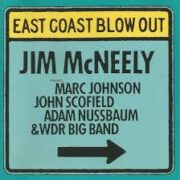

McNeely recorded four trio and small-group albums from 1976 to 1988. However, East Coast Blow Out from 1989 was when McNeely truly came into his own. The WDR Big Band is heard in full roar alongside major soloists John Scofield, Marc Johnson and Adam Nussbaum. All that complex ’60s-era pianistic harmonic information understood so well by McNeely the player was securely placed in service of full-band writing; the rock overtones of Scofield’s guitar were also fresh in this context. East Coast Blow Out is now considered a classic of the genre and a perennial source of inspiration for large-ensemble jazz composers.

McNeely recorded four trio and small-group albums from 1976 to 1988. However, East Coast Blow Out from 1989 was when McNeely truly came into his own. The WDR Big Band is heard in full roar alongside major soloists John Scofield, Marc Johnson and Adam Nussbaum. All that complex ’60s-era pianistic harmonic information understood so well by McNeely the player was securely placed in service of full-band writing; the rock overtones of Scofield’s guitar were also fresh in this context. East Coast Blow Out is now considered a classic of the genre and a perennial source of inspiration for large-ensemble jazz composers.

Many more McNeely suites followed, including collaborations with other high-level soloists. Some were recorded, including releases starring Renee Rosnes, David Liebman, Richie Beirach and Chris Potter. Key albums of McNeely himself featured with a band include Paul Klee (with complex yet fun “Ad Parnassum”) and Lickety Split (with notably charismatic “Extra Credit”). [Ed.: This magazine also recommends the out-of-print, not-streaming Group Therapy by the Jim McNeely Tentet, OmniTone, 2001.]

There’s a lot of great music in the McNeely discography; at some point an enterprising musicologist will make a valuable project going through all these terrific scores. A recent release was Primal Colors, which has not just the Frankfurt Radio Big Band but also the Frankfurt Radio Symphony. “Big band meets orchestra” experiments usually fail, but McNeely rose to the challenge and summoned a vast charismatic palette from this unholy union.

There’s a lot of great music in the McNeely discography; at some point an enterprising musicologist will make a valuable project going through all these terrific scores. A recent release was Primal Colors, which has not just the Frankfurt Radio Big Band but also the Frankfurt Radio Symphony. “Big band meets orchestra” experiments usually fail, but McNeely rose to the challenge and summoned a vast charismatic palette from this unholy union.

McNeely seemed to like all kinds of music and was perennially curious about new sounds. When confronted with a new orchestra, he disarmed the suspicious players by telling jokes and asking questions. His wit and generosity helped make him an excellent colleague, a sympathetic collaborator and a terrific teacher. He was also a devoted family man; he credited his wife, Marie, as “his beautiful pillar of strength” and his three children as sources of joy and inspiration.

Cancer is a terrible fate, but in some cases a slow descent enables a round of meaningful farewells. While he and his wife had retired to Maine, in late 2024, after confronting the diagnosis, the McNeelys returned to New York for treatment and caught up with many old friends.

McNeely stayed alive to witness a thrilling retrospective concert of his compositions on September 10 at the DiMenna Center performed by an 18-piece big band of renowned musicians and guest artists. His old friend and musical partner, Rufus Reid, was the Master of Ceremonies. One is hard-pressed to name a famous jazz musician Rufus Reid hasn’t played with, but that night he told the audience that studying composition with McNeely at the BMI Jazz Composers Workshop was a true highlight, and the best five years of Reid’s life.

In addition to his wife, Marie, Jim is survived by his children Clare, Grace and Peter McNeely, his daughter-in-law, Ashley McNeely, his grandson Andrew McNeely and his siblings Connie McNeely and Tom McNeely. JT