The wee early 1990s was a ripe, weird moment for jazz within the hip-hop and electronic dance music continuum. After the shock tactics of Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” a decade previously, everything was up for grabs:

A Tribe Called Quest crafted three dynamic, risky, back-to-back albums with bassist Ron Carter in the mix. Gang Starr rapper Guru’s solo album Jazzamatazz Vol. 1 welcomed Roy Ayers, Donald Byrd and Branford Marsalis into its groove. Certainly, Digable Planets’ smash hit “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat),” with its sample of James Williams’s “Stretching” (from the 1979 Timeless release Reflections in Blue by Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers), was historic.

Then there was London-based producer Geoff Wilkinson’s Us3, a British jazz rap ensemble, named for a 1960 Horace Parlan album on Blue Note. The group’s first LP, Hand on the Torch, used samples from Blue Note tracks produced by Alfred Lion, at the insistence of then label boss Bruce Lundvall.

The first result of the partnership between Blue Note and the ever-inventive Wilkinson? The global Top-Ten hit “Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia),” with an earwormy sample of Herbie Hancock’s “Cantaloupe Island,” and Blue Note’s first platinum-certified album.

Us3 continued making wildly contagious, funky jazz-hop albums with an increased sense of cinematic ambience until 2013 when health problems slowed Wilkinson’s roll. Rather than leave the game completely, he moved to composing music for licensing to the film, television and advertising business. Which brings us, naturally, to the 2025 return of Us3, and its new instrumental album, Soundtrack, releasing August 22.

Us3 continued making wildly contagious, funky jazz-hop albums with an increased sense of cinematic ambience until 2013 when health problems slowed Wilkinson’s roll. Rather than leave the game completely, he moved to composing music for licensing to the film, television and advertising business. Which brings us, naturally, to the 2025 return of Us3, and its new instrumental album, Soundtrack, releasing August 22.

Wilkinson’s new vision for Us3 and Soundtrack splits the difference between filmic Technicolor-inspired worlds, soulful jazz melodicism and the crispness of trap-hop rhythm.

Geoff Wilkinson spoke to JazzTimes in anticipation of Soundtrack’s grand premiere.

Soundtrack has more to do with cinematic jazz — think Gil Evans, Quincy Jones — than it does hip-hop, and yet it still holds the bump of fresh, clean modern rhythm as its key.

Right from the very beginning I’ve tried to make music that’s 50 percent jazz and 50 percent hip-hop, and I think the new album stays true to that principle, albeit in a different way regarding both genres. The hip-hop element has become more modern and up to date (with the trap beats), and the jazz element is, as you say, largely influenced by the great horn arrangers of the ’50s and ’60s, particularly Gil Evans.

What role does jazz hold for you now? The Blue Note stuff where Hand on the Torch got its Alfred Lion–based samples, or the present of jazz at its most boundaryless?

Jazz and hip-hop have a magpie-like tendency to liberally borrow from other genres in order to feather their own nests. That’s what makes things interesting, both types of music continue to change and evolve. Clearly Soundtrack was influenced by a particular period in jazz, but I wanted to update that cinematic vibe by fusing trap beats and relatively simple melodic themes with the harmonic intensity of the horns. I like the contrast. […]

It’s interesting that there has never been an “acid jazz” revival, and I think the reason for that is because jazz has become more infused in other genres now, and become more widespread and accepted. If Kendrick Lamar’s first album had come out in the early ’90s it would have been called acid jazz. If Gregory Porter had started in the early 1990s, he would have been called acid jazz too. We made our infiltration attempts by stealth [laughs].

Can you discuss Bruce Lundvall’s role in this?

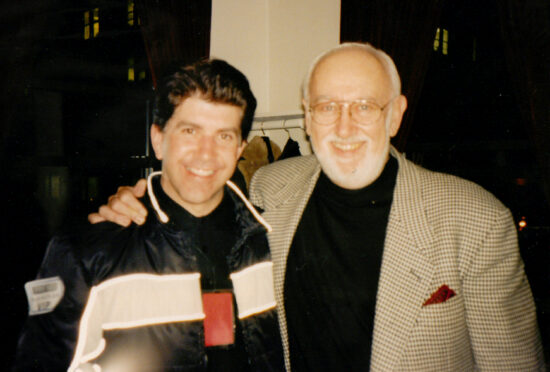

We did get some limited criticism for being a postmodern marketing vehicle for the Blue Note back catalog, but frankly I didn’t care. In my opinion the world is a bit better with more jazz in it. Ultimately it was Bruce’s decision to let us loose. That was a pretty radical decision, and to this day has not been copied by any other label in any other genre. In many ways it was a typical Blue Note thing to do and showed the progressive mentality of the label under Bruce. [Lundvall died in 2015 at age 79.]

Sampling was still a bit controversial then, but Bruce embraced it, and of course we made sure that all the original artists got paid properly. I had some fantastic conversations with Bruce; he was a fascinating man. But it wasn’t all about looking backwards, we had some great young British jazz talent on there too, which he also recognized. You talk about blurring the edges, and that was exactly what we were trying to do in the studio as well, to blur the boundaries of where the samples and live playing began and ended. Bruce loved that. It’s all music after all.

Were you a big old-school jazz head before Us3, or did it wind up being a means to an end?

I was definitely a big jazz head before I met the Blue Note people. Immediately before we signed the deal I was working at the Jazz Café in London as assistant to Jon Dabner, who opened the venue. Unfortunately, the club got into financial difficulties and went into receivership. Jon was kicked out and I took over booking the bands on my own. It was only nine months before a buyer was found but I loved it.

I was also DJ-ing there every Friday night for over two years, playing a mixture of funky jazz, jazzy funk and a bit of hip-hop. When I met the Blue Note people, I knew exactly what I wanted to do, I knew what I was talking about, and I think that gave them the confidence to go ahead with it.

Do you think platinum success with that first album changed the angle of Us3’s trajectory at all at the time?

I don’t think it changed the direction of the music, but in other ways it did. All of a sudden there was a demand to see it live. But the album was made by myself and my production partner at the time, Mel Simpson, with a sampler in a basement studio, with a variety of musicians and rappers coming in and out. We were producers. It had not even crossed our minds to do it live, or even how we would do it.

We had an almighty argument with our manager, who threatened to walk if we didn’t put a live band together. So we did. And it just went berserk from day one. The first live gig we ever did was in Japan, where “Cantaloop” first hit. It was in Osaka in June 1993, and from then on the band became a bit of a touring monster.

Can you discuss composing and creating for licensing to film, television and advertising?

The first library music album I made was in 2008. [Ed.: Library music, or production music, is made for a production music library, which then licenses it for use in various entertainment media.] At the time I was renting studio space in a block along with about 20 other artist-producers. The guy next door used to be a big pop producer but now solely made library music, and he explained what it was and how it worked, so I thought I would try it.

I did about three or four albums at the time and got them signed to different labels. After I got ill in 2014, I didn’t think I would work again, gave up the studio space and sold all my gear. It was only after about six months that I started to feel much better — I was enrolled on a cardiac rehabilitation scheme — and felt like I wanted to work again. I bought a new Mac Mini, installed Logic and set about learning some new software.

The thing about library music is that it’s all business-to-business, it’s not for sale to the general public, so there’s no demand to do promotion or marketing. No touring! That was appealing to me, as I could just scratch my creative itch without putting myself in the wider glare of the world.

To date I have had over 1,000 library tracks signed. To put that in context, in the first 20 years of Us3 there were less than 150 Us3 tracks released (nine albums). I don’t think I’ll ever stop doing library music now. It felt like being let off a leash. I could and did experiment by working in lots of different genres, which I found to be liberating. Undoubtedly it also honed my songwriting skills.

When did your cinematic brand of music begin to morph into something jazzier, distinctly melodic and Us3-like?

I had done several moody trap albums as library music, and loved the ethereal spaciness of it, as well as the uniqueness of the drum patterns and sounds involved. But my imagination started to run away with me, and I started wondering what it would sound like with some jazz on top. I think it was probably listening to Sketches of Spain one day that made me hit on the idea of fusing some Gil Evans–style horn arrangements with the trap beats.

I had already flirted a bit with this back in 2003 when I made an album in collaboration with the sax player Ed Jones. We called ourselves ed/ge and the album was called A view from the… Ed had done almost all of the horn arrangements on every Us3 album and was in the Us3 live band since day one.

I had already flirted a bit with this back in 2003 when I made an album in collaboration with the sax player Ed Jones. We called ourselves ed/ge and the album was called A view from the… Ed had done almost all of the horn arrangements on every Us3 album and was in the Us3 live band since day one.

In fact, that album came about after a lively conversation on the tour bus about how and why big bands weren’t fashionable any more, and we made a vow together to make a modern hip-hop-inspired big band album, and so we did. Several tracks on that album were directly influenced by two particularly maverick horn arrangers. “King Don” was our homage to Don Ellis, and we also did a cover of Gil’s “Las Vegas Tango.”

I remembered that keyboardist Mike Gorman, who I’d worked with extensively in Us3, live and studio, had played me some orchestrations for horns and strings that he had done for Kid Creole a few years before. Mike has also had his own big band project and saw them live at Spice Of Life in London’s West End years ago.

Initially this was not intended to be an Us3 album. I thought it was a side project, and only while mixing did I become convinced I had actually made an Us3 album.

Trap is an important part of what this new album is — likely as much as early ’90s hip-hop was to the first two Us3 albums. What is so durable and applicable within the trap groove?

As a generalization, I would say that a trap beat is about syncopation of different drum sounds, and that often varies in intensity within a track. Sometimes space is more important, sometimes density. That can also be applied to much of Gil Evans horn arrangements too. That was really the lightbulb moment for me, when I realized that was something the two seemingly disparate things had in common.

I appreciate that the songs on Soundtrack have no vocals yet still manage to convey something of the purpose-message of a track like “What Have We Done?” with its environmental concerns, or “Resist the Rat Race.” How do you ensure those messages are conveyed without lyrics? Do you feel that production music has made you keener at conveying emotion through pure sound regardless of written message?

Yes definitely. I am a much better producer and writer now without a doubt. And I’m still learning, I never want to stop learning. After I got ill, I really did go through an emotional wringer. I had to have six months of psychotherapy to get through it, which was a great help. Maybe this album is some kind of catharsis for me.

Are you curious to stay with Us3 and see what a vocal album would be or could be in 2026? And how would it differ from the spoken-sung vibe of previous Us3 works?

Yes, I have been bitten by the Us3 bug again. I have some new ideas but that’s still formulating. Soundtrack is the first album I’ve released in the streaming era, and there is something I’ve encountered that is bugging me. Playlists rule everything now, and there isn’t an obvious “playlist home” for the Soundtrack album. […] We did come across this with “Cantaloop” at the start, especially with physical product. Should it be in the jazz section or the hip-hop section?

My answer was both, obviously, but it gave the marketing guys a bit of a headache. My worry with the dominance of genre-specific playlists is that it encourages artists to make music that fits onto a playlist rather than trying to create something new. Consequently, does the streaming era encourage conformity? I hope that’s not true. JT