What sort of world is it where the multi-hyphenate behind pop culture’s bawdiest social critiques can also be a suave singer hellbent on shedding new light on big-band jazz and the Great American Songbook?

Seth MacFarlane’s world — he being the animator, screenwriter, producer, director and voice artist behind animated heavyweights Family Guy and American Dad!, as well as the vocalist-curator of nine Tin Pan Alley–drenched albums since 2011, the latest of which pays tribute to the greatest male vocalist of all time, Frank Sinatra, and a treasure trove of unearthed songs and orchestrations destined for his catalog.

As an artist working within the theatrical realm, the emotional drama and nuance of Sinatra’s finest vocal interpretive work is something that MacFarlane never takes for granted. “As a singer and an interpreter, no one can touch him,” he says.

“There’s a reason that he stands alone, still, amid a cast of characters from that era that were all truly great vocalists. There is just something in the way that Sinatra acts out a story, the way that he allows the role of the orchestrator and the band to play a part in the recording — an achievement only rivaled by Nat ‘King’ Cole — that makes his recordings a uniquely rich experience.”

Beyond Ol’ Blue Eyes

At no time during Lush Life or his other eight albums do you hear MacFarlane impersonating Ol’ Blue Eyes and his sauntering, clearly enunciated phrasing. Shared swagger aside, there is no imitating Sinatra — which is pretty great when you consider MacFarlane’s power of mimicry as an animation voiceover artist.

“I think that every vocalist post-1955 who does this music is influenced by, and indebted to, Sinatra in the same way that every animated television series post-1990 is influenced by The Simpsons,” Seth says, touching on a highlight of his day job. “We’re always going to be in the shadow of this towering figure who rewrote the vocal rulebook. I’m glad that I did this Sinatra album now because I’ve had time to settle into a style, a method of interpreting lyrics that brings my own vibe to the table.”

Besides, Sinatra is not the only object of MacFarlane’s reverence. Surprisingly, he brings up lounge singer Steve Lawrence as well as Gordon MacRae, the actor and booming baritone behind two of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s most masculine musicals, Oklahoma! and Carousel. “MacRae’s was a voice that I was in awe of because it’s always accessible even after a night of drinking — and then he’d end each song on a silky falsetto note that came from out of nowhere. He had the range of an opera singer at their peak, yet MacRae was singing pop music and showtunes. Steve Lawrence too is wildly underrated. This was a guy who sounded so relaxed and at ease, yet had a rich, natural instrument. He never phoned it in. When I record, that’s what I watch out for. They made it sound so easy, yet if you analyze the recordings, they’re never giving less than 100 percent. As Sinatra pointed out, there’s a big difference between crooning and singing. The swagger? It’s secondary. It’s garnish.”

The Inner Sanctum

Though forever bewitched by Sinatra, it was MacFarlane’s getting to know Tina and Frank Sinatra Jr. (who co-starred several times as himself on Family Guy) that brought him closer, in a literal and figurative sense.

“I had seen Frank Jr. on The Sopranos and thought if he had done that show, that maybe he would do ours,” says MacFarlane. “He did, and came in ready to go and up for anything. We wrote songs for him and he sang with Brian and Stewie, so that was a blast. He was also a walking encyclopedia of music from the big-band era and the golden age of vocal standards. The orchestras from that era that he turned me onto, that I’d never heard of, were amazing. Like the Sauter-Finegan Orchestra. Who were they? Frank Jr. knew, and he put them on my radar.” [Ed.: Eddie Sauter and Bill Finegan, both important composer-arrangers, co-led this sprawling, money-losing, quasi-Third Stream project throughout the 1950s.]

When Frank Jr. passed away, MacFarlane got closer to Tina. “She’s an amazing steward of her father’s legacy but also a great hang. She can smell bullshit and what she saw in me was a love of her father’s music. And on his 100th birthday, with an orchestra in tow, we got to sing many of Frank’s favorites — that’s a cool way to have a birthday party.”

At that very party, Tina gave MacFarlane a ring with the Sinatra family crest, of which there are fleetingly few. “Tony Bennett got one. I was immensely grateful… I wear it during every live show and recording I do.”

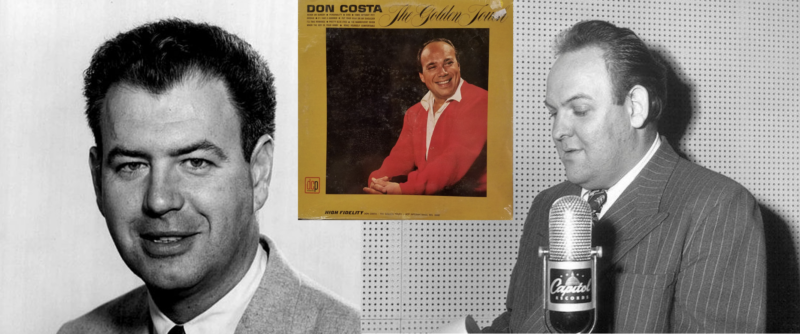

He was asked to acquire the Sinatra music archive from the family estate — some 1,800-plus charts and more — and MacFarlane grew interested in the songs written or arranged for Sinatra that fell by the wayside. Gathering MacFarlane’s longtime producer-arranger Joel McNeely, conductor John Wilson and engineer Rich Breen (who insisted on reel-to-reel tape), the team begin to dissect the once-lost arrangements of Nelson Riddle (nine), Billy May (two) and Don Costa (one).

“We knew that this was something we couldn’t screw up,” says MacFarlane. “It had to be done in the way Nelson Riddle would want these arrangements to be heard. And we had fun doing it.”

MacFarlane and the team were guided by Sinatra Enterprise archivist Charles Pignone when dealing with songs like Gus Kahn’s “Flying Down to Rio,” which was cut for the Come Fly with Me album but never used. There was a gorgeously odd Nelson Riddle arrangement of Johnny Mandel’s “The Shadow of Your Smile” that MacFarlane is planning for another volume. There was the melancholy “How Did She Look?” planned for the ruminating romance epic Only the Lonely but never cut. “There were 1,200 boxes of Sinatra’s that were mostly unmarked, so the only way to know what was there was to play them. So we got an orchestra to play them, and that was a real voyage of discovery.”

Riddle orchestrations such as “Shadows,” “Who’s in Your Arms Tonight” and the longing-filled “How Did She Look?” from 1958, as well as “When Joanna Loved Me” from 1977, are among the arranger’s finest moments. But it is Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life” that really tested Frank.

“It’s a beast,” says MacFarlane of the slippery, sophisticated bends and twists of a song that Johnny Hartman and John Coltrane made their own. “It is as esoteric an arrangement as Riddle ever wrote, and a tough melody too. You can guess why Frank let it fall by the wayside. Nat ‘King’ Cole did it right but he was a pianist and had that edge. It was hellish for me.” [Ed.: According to biographer David Hajdu, Strayhorn did not like (putting it mildly) the Pete Rugolo arrangement that Cole used in 1949.]

“I’ve been told that I have vocal cords of iron that show up when I need them,” says MacFarlane about maintaining his voice as a singer and a vocal actor. “That said, doing Quagmire, Stewie and Peter for extended times isn’t necessarily great for my singing voice. I get this from my father, though: I have vocal cords that can take a beating.” JT